How journalists work under Russian occupation in Crimea

Working as a journalist without becoming a propagandist under occupation in Crimea is challenging and risky. But there are still people who do it. On the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists, we shed light on the challenges that journalists in Crimea endure

Since the full-scale invasion, Crimea's occupying authorities have strived to maintain strict information control and isolation on the peninsula. They have intensified pressure and surveillance on individuals who don't align with the Kremlin's narrative, attempting to silence dissent. New administrative and criminal laws have been introduced, targeting those who expose Russian war crimes or voice anti-war sentiments. The mass conscription of Crimean Tatars into the Russian army, which some consider a form of hidden genocide, has led to a surge in refugees from the region.

Repression has escalated significantly. Over the past 20 months, dozens of individuals have been added to the list of Crimean political prisoners. As per information from the Representation of the President of Ukraine in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, since February 24, 2022, 65 individuals from Crimea, Kherson region, and Zaporizhzhia have been kidnapped and sentenced on the occupied peninsula, becoming prisoners of the Kremlin.

The total number of political prisoners in Crimea has now reached 189, with 123 of them being Crimean Tatars. Security forces have started prosecuting even previously overlooked groups of people. For instance, women like Iryna Danilovych have not been spared, and lawyers are discouraged from defending political prisoners facing predetermined sentences.

Their main focus is on those who attempt to share information about the persecution with the outside world, including citizen journalists and activists. Currently, over 15 journalists who worked in Crimea, most of them Crimean Tatars, are detained in Russian prisons and pretrial detention centers.

Administrative cases are used as a final warning before detention

Kulamet Ibraimov's experience as a journalist includes multiple arrests, two administrative detentions, searches of his parents' home, and frequent visits from Crimean security forces with written warnings about "violating the law" and "participating in unauthorized activities." This is how the occupying authorities interpret a reporter's on-the-scene work.

In 2019, Ibraimov began reporting on the searches, arrests, and trials of political prisoners for the Crimean Solidarity Association and the Russian opposition publication Grani. Grani provided him with a press card and assigned editorial tasks, confirming his official status and intending to shield him from security forces' pressure. Despite this, he faced multiple detentions while on the job, including incidents in November 2021 and in January and July 2023.

During the winter of that year, the occupying police issued an administrative report against Ibraimov for a "mass simultaneous gathering of citizens that disrupted public order" (as per Part 1 of Article 20.2.2 of the Code of the Russian Federation on Administrative Offenses). The court subsequently sentenced him to 12 days of administrative arrest. In the summer, he faced another case under the same article and circumstances, leading to a 5-day detention.

On each occasion, Ibraimov carried his press card and an editorial assignment, yet the security forces detained him with promises to "resolve the matter at the local office." In July, Kulamet was detained by the occupation Supreme Court of Crimea along with her colleague Lutfie Zudiyeva and 11 others attempting to attend an open hearing regarding political prisoners. The security forces claimed they had received a complaint on the hotline about people near the court "obstructing citizen passage." However, Ibraimov was not even with the others at the time; he was detained following a conversation with a bailiff.

At the local police department, individuals were interviewed and pressured to provide fingerprints and saliva samples. Ibraimov and Zudieva refused to comply. In response, security forces threatened Zudieva with an administrative protocol for disobeying the police (as per Article 17.7 of the Code of the Russian Federation on Administrative Offenses), despite the voluntary nature of these procedures under Russian law. They attempted to learn from Kulamet to whom among his colleagues he had sent recorded videos, which were later published. They implied this could be associated with a crime and that he was "shielding" potential violators.

In the end, both journalists (along with three more relatives of political prisoners) were charged with causing a disturbance by being present with a large group of people. A court official named Yuriy Kholodkov filed the charges against them. He said that when he arrived at the court, a group of people, who appeared to be from the Caucasus region, had already gathered there, and some of them were blocking the entrance to the court.During the trial, two individuals, Artem Sklem, a former Russian army worker, and Vasily Kashkanov, a retired military personnel, testified about the incidents. They both claimed that in the morning, they saw 10-15 people who “did not appear to be of Slavic origin” near the court.

All of the individuals, except for Ibraimov, were fined by the judges Galina Tsyganova, Maria Domnikova, and Nataliya Urzhumova. The fines ranged from 12,000 to 15,000 rubles. Kulamet, who had previously violated court orders, was sentenced to 5 days of administrative detention.

Lutfie Zudieva expressed her concern about the court's decision, saying, "I believe they are trying to restrict our right to attend trials of political prisoners and express our views. It seems like there's no real law; the law is controlled by the security forces, the FSB, and the police."

Various organizations, including the Committee for the Protection of Journalists, Reporters Without Borders, the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine, and several Ukrainian and international human rights groups, came forward in support of the journalists, demanding that Russian authorities stop their persecution.

These "administrative charges" for attending court sessions, posting on social media, or live-streaming from the scene of an incident are common tactics used to put pressure on activists, human rights defenders, and citizen journalists. Security forces detain people for "unauthorized mass gatherings" (often citing Articles 20.2 and 20.2.2 of the Code of the Russian Federation on Administrative Offenses) or for displaying symbols associated with banned organizations (Article 20.3 of the Code of the Russian Federation on Administrative Offenses), or for allegedly discrediting the Russian army (Article 20.3.3 of the Code of the Russian Federation on Administrative Offenses). Even if there are errors, inconsistencies, or falsifications in the records, the judges handling these cases often disregard objections from the defense and issue guilty verdicts. Initially, this might result in fines, but for repeat offenses, it can lead to more serious administrative penalties.

In Crimea, every year, many "administrative charges" are filed. During a year and a half of the full-scale invasion, the occupying security forces initiated over 500 administrative proceedings, even targeting human rights defenders and lawyers, all based on one accusation of "discrediting the Russian army."

However, the worst consequence isn't just spending two weeks in detention for no reason. It's the fact that you end up on the radar of the FSB or The Centre for Combating Extremism. These "administrative penalties" lead to more pressure, searches, and, in the end, fabricated criminal cases. Citizen journalists like Remzi Bekirov, Osman Arifmemetov, and Ruslan Suleymanov are examples of this. They were initially given administrative sentences for "unauthorized mass events" and are now serving 14 to 15 years in high-security Russian prisons for "participating in a terrorist organization."

The day after the most recent administrative arrest, security forces searched Kulamet Ibraimov's mother's house, where the journalist resides. At 7 in the morning, ten members of the Center for Combating Extremism entered the house, confiscated the family's phones, and conducted searches in the house, cars, and sheds, and went through all the books and documents.

Ibraimov believes that this "visit" was connected to his work because during the search, security forces indirectly warned his relatives to make him stop working as a journalist: "They said if I don't quit [journalism], things will end badly for me."

No one is safe from being involved in a criminal case

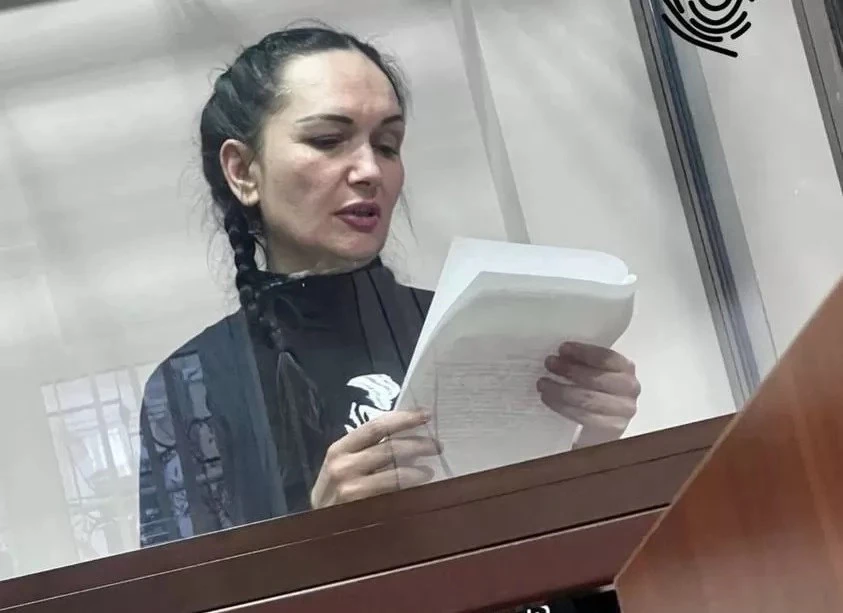

Iryna Danilovych is 44 years old. She spent the last year and a half of her life in a Russian prison. During this time, she experienced abductions, threats, and intimidation. She personally witnessed what it's like to be falsely accused and treated inhumanely in a detention center. She even went on a hunger strike and lost most of her hearing in one ear. Iryna Danilovych is a nurse, a citizen journalist, and a political prisoner. Her story highlights a worrying new trend in Crimea, where security forces are bringing unfounded charges against women and imprisoning them for years.

On April 29, 2022, Danilovych was coming home after her night shift at a rehabilitation center. It was a Friday morning, and she was waiting for a bus at a stop in Koktebel when she was forcefully taken by four security officers to an unknown location. She was essentially kidnapped because her relatives were not given any legal documents explaining where and why she was being taken. Her lawyer, Ayder Azamatov, spent 13 days searching for her in various Crimean detention centers and pre-trial detention centers. However, the security forces claimed to have no knowledge of her whereabouts. Nevertheless, on May 7, she was put in custody by an occupation court, with an appointed lawyer present, under suspicion of "possessing an improvised explosive device" (as per Part 1 of Article 222.1 of the Russian Criminal Code).

Such kidnappings are common in Crimea. Unidentified men, often without any official identification, either pick people off the street or, after searching their homes, force them into a minibus and take them to an unknown place.

For several days, the families and lawyers of those who are taken cannot find them. Meanwhile, the law enforcement officers in Crimea subject innocent individuals to coercive tactics, such as keeping them in hidden places, intimidating them, and using physical violence to force confessions.

The same kinds of pressure are applied by the Crimean security forces to those who are coerced into giving testimony for the prosecution. We've seen this in cases like Nariman Dzhelal and the Akhtemov brothers, as well as with Enver Krosh, Ruslan Paralamov, and Nariman Ametov. The list of such cases is not limited to just these examples.

Iryna Danilovych explained in court that she had been held in a basement by the FSB in Simferopol without access to a lawyer. During her captivity, she was questioned about her ties to Ukrainian special services, subjected to threats, physical abuse, and choking, and was denied regular access to a restroom or proper meals. A week later, they told her she could go home if she made a video statement expressing no complaints against the FSB agents and signed some documents.

When she attempted to read the content of those documents, one of the captors threatened to kill her in a forest. Iryna Danilovych ended up signing all the documents, including blank forms. Following this, law enforcement claimed she was in possession of explosives. They alleged that they found 200 grams of explosives in a glasses case within her bag. Later, investigators asserted that the explosives were discovered in her possession immediately after her arrest, and that she had willingly entered the FSB building because she had no place to stay in Simferopol.

Before her abduction and arrest, Iryna Danilovych was an active and well-known figure in Crimea. She wrote and produced videos about the trials of political prisoners for the "Crimean Process" and "INzhyr media" projects. She collaborated with human rights organizations and led the Facebook group "Crimean medicine without a cover," where she addressed issues within the healthcare system. She also headed the Crimean branch of the trade union "Alliance of Doctors." Her outspoken stance and visibility did not escape the notice of law enforcement.

The trial of Iryna Danilovych was challenging to follow due to the FSB's efforts to silence her lawyers, Ayder Azamatov and Oksana Zheleznyak, who were made to sign nondisclosure agreements. They were prohibited from sharing legal documents pertaining to the case with the media or providing commentary on the investigation's progress. Nonetheless, the lawyers couldn't decline to sign these agreements, as refusing to do so would have led to the appointment of a state lawyer controlled by the system, which would have hindered their ability to defend Danilovych.

A non-disclosure agreement is a common tactic used by the FSB in cases involving alleged treason, espionage, sabotage, or possession of explosives. For instance, they demanded that lawyers for Vladyslav Yesypenko, Ivan Yatskin, Yevhen Panov, and other Ukrainian political prisoners sign such agreements. This is a way for security forces to prevent public discussion of court proceedings, as it's impossible to dispute facts that are prohibited from being discussed.

The FSB also tried to charge Iryna Danilovych with treason. During a house search, which was conducted with many violations and without legal representation, individuals in plain clothes told Iryna's father, Bronislav Danilovcyh, that his daughter was under administrative arrest for ten days for "transferring non-secret information to a foreign state." In the basement, they demanded that she confess to connections with Ukrainian special services for a week without mentioning any explosive substances. Eventually, Iryna was arrested and convicted of possessing explosives, while the FSB continued to investigate her for "treason."

"In the specified time period, Danilovych Iryna... was found in possession of a homemade explosive device of the high-explosive fragmentation type... The means of detonation was a military electric detonator, and the means of concealed transportation was a glasses case. The ready-made components included medical syringe needles, as indicated in the indictment. She carried the device in a black cloth bag until it was discovered on April 29."

During the trial, the journalist explained that her bag was searched by law enforcement officers immediately after her abduction in the FSB building, and the process was recorded on video: "I distinctly remember when the FSB employee opened my case, claimed it contained glasses, and checked it with a metal detector. There was nothing in that case—no explosive devices, no broken needles, and not even Krona batteries were anywhere near my bag. All of this was captured on video."

The prosecutor did not explain where Danilovych obtained the explosives and why. However, Judge Natalia Kulinskaya did not inquire about these details. The trial had several violations of the right to a fair trial. Kulinskaya dismissed important requests from the defense and openly supported the prosecution. For instance, the defense was not allowed to question 15 witnesses or examine material evidence. Instead, the prosecutor read out interrogation reports of witnesses conducted by FSB officers without giving Danilovych and her lawyers the chance to cross-examine them in court.

Most notably, Kulinskaya's determination to convict Danilovych, despite evidence of her innocence, is evident in her disregard for Iryna's abduction, her claims of torture and threats by FSB officers, and the clear case falsification.

One of the witnesses who claimed to have seen explosives in Danilovych's bag, Konstantin Vysokoglyad, was revealed to be an employee of the occupation police in the Bakhchysarai district, even though he falsely claimed to be a "self-employed" "representative of the public" in court.

"People with unchecked power and impunity abduct individuals, unlawfully detain them, subject them to torture, and rob their homes. Then, to cover up or justify their actions, they fabricate criminal cases against these people, planting explosives, drugs, or any other false evidence," — these were Iryna Danilovych's final words in court. Kulinskaya sentenced her to 7 years in prison and a fine of 50,000 rubles.

While in pre-trial detention, Iryna's health deteriorated irreparably. Without medical attention, she developed acute otitis media, leading to deafness in her left ear, neurological disorders, and brain damage. She fainted several times on the way to court from Simferopol to Feodosia, suffering from a constant headache, ringing in the ears, and dizziness. Although an ambulance was called multiple times during the hearings, neither the prosecutor nor the judge responded. Since the detention center administration ignored her request for proper medical examination for months, Danilovych even initiated a hunger strike.

This treatment of Crimean political prisoners has been a longstanding practice of the occupying authorities. The detention center conditions are so deplorable that numerous previously healthy individuals develop severe chronic illnesses, and those who had pre-existing conditions find themselves on the brink of life and death. Human rights activists have compiled a list of Kremlin prisoners with serious illnesses and disabilities who may die in captivity due to the lack of medical care. It was named after two Ukrainian political prisoners who died in Russian prisons during the full-scale invasion in February 2023. This marked the first such occurrence during the years of Crimea's occupation.

"I've been trying to see a doctor for a month. Instead, they send me to paramedics who tell me to 'cut your veins and get away from us," Iryna recounted one of her interactions with prison medics in December of last year. Following the verdict, she was transferred from Crimea to a Russian prison in the Stavropol Territory. However, even there, Iryna Danilovych continues to be denied proper medical care and the medications sent by her relatives.

Everyone can face criminal charges

Vilen Temeryanov became a citizen journalist in 2018. He joined Crimean Solidarity to challenge the perception of "Crimean Tatar terrorists." He made videos, wrote news, and reported on court hearings.

The Russian police started targeting Vilen about a year later. In November 2019, he interviewed people near the Southern District Military Court in Rostov-on-Don, where many of Crimea's political prisoners were tried. The police tried to stop him from filming and detained him for identification.

After this, the security forces frequently tried to hinder Vilen's work. In November 2020, he was detained near the Crimean Garrison Military Court in Simferopol while filming relatives of the accused with posters. He faced two administrative charges - one for "organizing a mass gathering that disrupted public order" and another for "not following COVID-19 safety rules."

Vilen defended himself, saying, "I was documenting people near the court. Some didn't like it, but the police can't restrict a journalist's work. I wore a mask and followed health guidelines. I believe I'm not guilty of the first charge, and I don't think the second one applies either."

In November 2021, he was detained again. This time, he was covering a gathering of about fifteen hundred Crimean Tatars who had come to meet lawyer Edem Semedlyaev after his administrative arrest. The Russian Guard arrested 32 people, including five "Crimean Solidarity" journalists. They were all given 10 to 14 days of administrative arrest for "participating in a gathering that disrupted public order."

Vilen's wife, Elmaz Gaziyeva, saw this as a "final warning" before the criminal case: "He wasn't fined this time; he got 14 days in jail. After his release, we discussed it, and I asked if he understood that they were after him. He said, 'Yes, after that arrest, I'm sure.' Despite knowing the risks, Vilen remained committed to journalism."

A criminal case was opened against the journalist on August 11, 2022, during the full-scale invasion. He was accused of being connected to the Islamic political party Hizb-ut-Tahrir, which Russia considers a terrorist organization.

This party's goal is to promote the Islamic way of life in Muslim nations and spread Islamic ideology worldwide. They focus on political and ideological activities and avoid violence. Russia is one of the few countries that labels Hizb ut-Tahrir as a terrorist organization, a decision dating back to a 2003 ruling by the Russian Supreme Court. This decision was not publicized for several years and lacked a clear rationale. Human rights activists consider those convicted of involvement in the party to be political prisoners.

Before the annexation of Crimea, law enforcement had no issues with Hizb ut-Tahrir supporters who openly expressed their views and organized events on the peninsula. However, after the occupation, these individuals became targets for the FSB, and Article 205.5 of the Russian Criminal Code became commonly used on the peninsula.

Three days after the explosions at the military airfield in the village of Novofedorivka, Saky district, security forces searched Temeryanov's home.

Shortly after, Russian propaganda channels began spreading information that the special services had uncovered another "group linked to Kyiv." Allegedly, they arrested terrorists in Dzhankoy, once again targeting Crimean Tatars. This is according to lawyer Emil Kurbedinov, who is defending the accused. However, there is no concrete evidence linking this case to subversive activities in Crimea.

The accusation against Vilen Temeryanov is based on the testimony of hidden witnesses and banned Islamic literature supposedly found at his home, which the journalist claims the security forces planted during the search. Additionally, the case file contains covert audio recordings of discussions in local mosques and private homes, where topics like religion, politics, the persecution of Muslims, and criticism of Russia are discussed.

Since 2014, 106 men have been arrested in Crimea under similar charges, with most receiving sentences of up to 20 years in prison. The Secretary of the Security Council of the Russian Federation, Nikolai Patrushev, continually claims they are "preventing terrorist attacks" on the peninsula.

Security services often create cases against Crimean Tatars by alleging they support certain ideologies, rather than needing to prove they were planning terrorist attacks. They rely on a limited set of evidence, such as incriminating statements from confidential witnesses, often naming acquaintances or individuals pressured by the authorities. They also use conclusions from examinations conducted by biased experts based on hidden video recordings of meetings. These meetings usually involve discussions on various topics, primarily related to Islam. The third piece of evidence is Islamic literature and notes found (or planted) by the FSB during searches, which often do not prove anything beyond the person's religious beliefs.

The documents fail to mention that Temeryanov is a journalist, even though he had a press card and editorial tasks with him during the search.

The criminal case revolves around two main charges: "participation in the activities of a terrorist organization" and "attempting a violent overthrow of the Russian Federation."

From a legal standpoint, this case is highly questionable. It resembles many similar cases against activists, citizen journalists, and religious figures. The FSB claims to "uncover" 5-6 such "violent overthrow" attempts in Crimea each year, alleging they thwart the activities of "terrorists," according to Kurbedinov.

Vilen Temeryanov quickly told the FSB that he's a Ukrainian citizen, so Russia should treat him according to the IV Geneva Convention, which protects people from being unfairly treated by Russian authorities and courts. However, as in many similar cases before, the occupation authorities, prosecutors, and courts ignored his claim. They see all Crimeans as Russians.

Vilen Temeryanov's case is now being heard in the Southern District Military Court in Rostov. He could face up to 20 years in prison. He's likely to be found guilty when the trial ends in a few months. During the whole time of the occupation, Russian courts have only acquitted one person in this category of cases—Ernes Ametov, a citizen journalist of Crimean Solidarity. However, the prosecutor's office managed to overturn this acquittal, and in the retrial, a new set of judges sentenced Ametov to 11 years in a strict regime prison.

Crimean Tatar journalists and activists often get accused of being involved in terrorist activities, while ethnic Ukrainians end up in prison on charges of treason, espionage, sabotage, and possession of explosives. These charges have become increasingly common in recent years. For instance, Radio Svoboda journalist Vladyslav Yesypenko's case is a clear example.

Since 2016, Yesypenko occasionally worked anonymously in Crimea, and his articles were published by "Krym. Realii" without his name. However, he still got arrested and faced false criminal charges. FSB officers detained him on March 10, 2021, and a few days later accused him of having "connections with Ukrainian special services" and "illegally storing and transporting an improvised explosive device."

"Yes, I did carry the mentioned explosive device during my trips around Crimea, where I interviewed Crimean Tatars about the illegal demolition of their homes by Russian authorities, recorded the effects of drained reservoirs, and surveyed the residents of Simferopol," were Yesypenko's initial statements under torture with electric shocks. These statements were documented by Vitaliy Vlasov, a senior investigator with the Crimean FSB. In September 2023, Vlasov, along with a colleague from the FSB, the prosecutor, and the judge in Yesypenko's case, faced sanctions from the European Union.

During the first court hearing, when the journalist had a lawyer present, he denied all the confessions and described how he was tortured. He said, "They stripped me naked and attached copper wires to my ears. I tried to resist, but since I was naked and in handcuffs, I couldn't do anything. The pain was unbearable; it felt like my brain was boiling, and my eyes were about to burst. I screamed and begged them to stop, but they didn't."

When the journalist's case went to court, the charges related to Ukrainian intelligence were dropped from the indictment. Instead, Yesypenko was accused of taking a hand grenade and its fuse from a hidden stash prepared by unknown individuals, claiming it was for his own safety. He then picked up the explosive device and transported it in a car.

In February 2023, Judge Dlyaver Berberov sentenced Vladyslav Yesypenko to six years in prison and fined him 110,000 rubles. The court never clarified which law enforcement officers discovered the grenade in his car or under what circumstances.

***

Working as a journalist in Crimea has become increasingly challenging over time. Gathering information on-site and sharing it beyond the peninsula's borders has grown more perilous. Hoping for protection from official status or professional solidarity is futile.

Initially, the occupying authorities expelled independent media from Crimea, then foreign and Ukrainian journalists, and muzzled local voices. Presently, citizen journalists are being arrested, particularly on charges related to terrorism and sabotage.

The number of political prisoners is rising, and their sentences are getting harsher. Yet, the notion of freedom of speech cannot be obliterated. When some incarcerated journalists are replaced by others who are willing to carry on their work, despite the risks and grim prospects, the spirit of free expression lives on.

This text is part of the investigative journalism project "Protecting the Frontline 3," funded by UNESCO and executed by the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR). The authors bear sole responsibility for the content of this text, which does not necessarily reflect the views of UNESCO or the Institute for War and Peace Reporting.

- News